In Baseball Hall of Fame reading, this piece features comments on books about Al Kaline, Harmon Killebrew, Billy Williams, and Rod Carew.

Originally published January 1, 2014 and February 13, 2014 at Fansided Radio:

With Derek Jeter’s announcement of his retirement at the end of the 2014 baseball season, there is no doubt that he will be inducted in Cooperstown in the summer of 2020. In doing so, he will join fellow baseball greats in baseball immortality. Over the last few days, I’ve been reading some of the biographies and memoirs released by Triumph Books. By no means am I finished but am only just beginning with my Baseball Hall of Fame reading.

After reading a book by the late Ralph Kiner and one about Ernie Banks, I moved on to Al Kaline, Harmon Killebrew, Billy Williams, Fergie Jenkins, and Mike Schmidt. All these books have been enjoyable and very well done. (Unfortunately, the reviews of the Kiner, Jenkins, and Schmidt books were lost to the internet. New reviews have since run for both Fergie Jenkins and Mike Schmidt.)

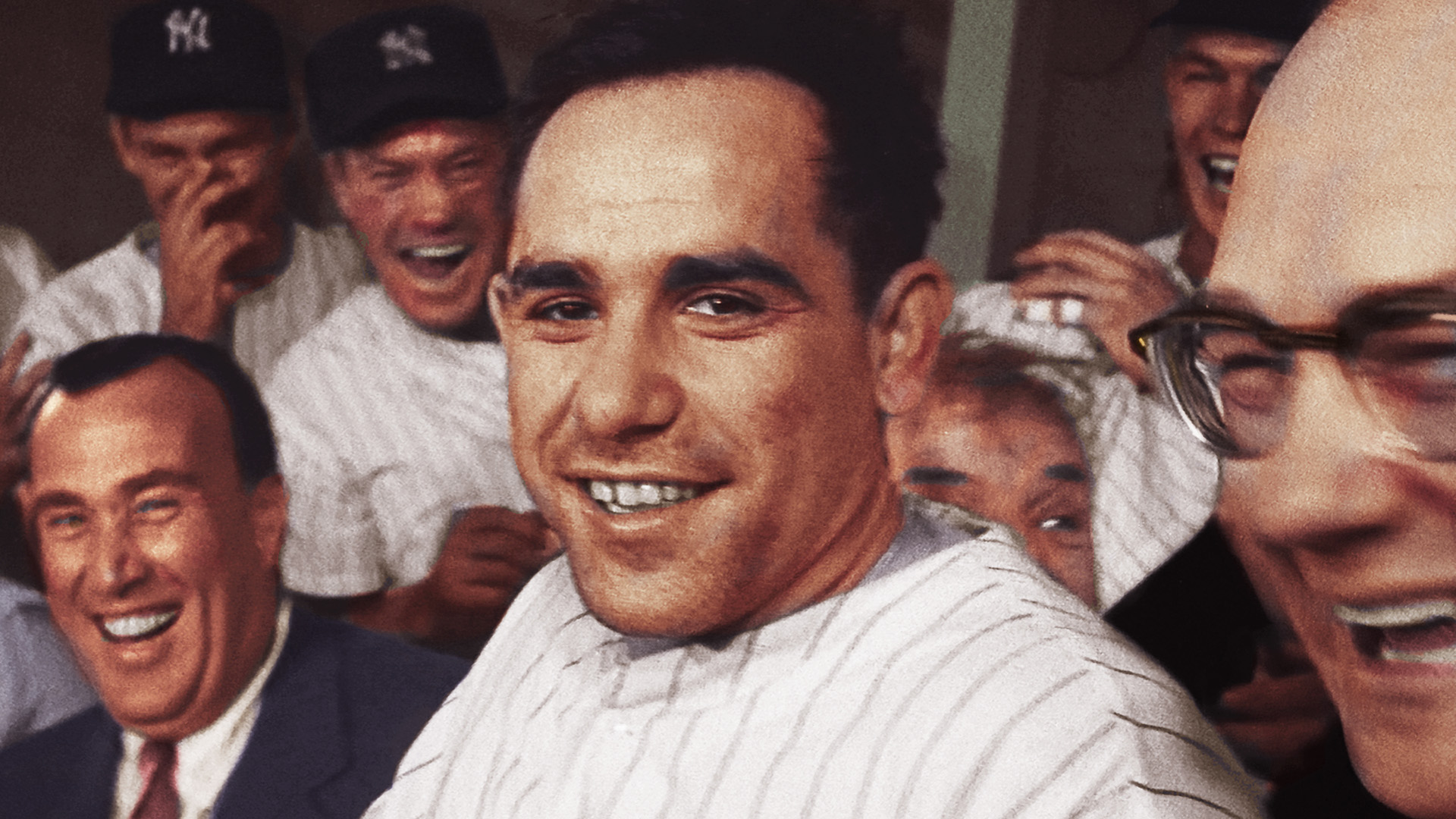

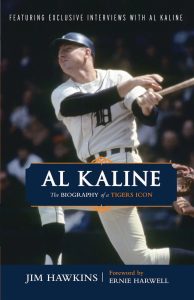

In Al Kaline: The Biography of a Tigers Icon by longtime Detroit sportswriter Jim Hawkins, we have the definitive portrait of the man they call Mr. Tiger.

While other players are synonymous with the Motor City, Kaline has been a part of the Tigers franchise since signing with the team as a bonus baby in 1953.

Hawkins does a splendid job in telling the story of Kaline, who grew up on the “wrong side of the tracks” in Baltimore. The son of parents that worked at a factory and distillery did not stop Al’s dream of getting to the big leagues.

Other biographies don’t have the pleasure of being able to interview their subject but Hawkins was able to do that with Kaline and sheds light on Kaline’s many accomplishments.

The original plan called for Kaline to ride the bench for the mandatory two years before hitting the minor leagues for seasoning. That never transpired as Kaline became the young player to win the American League batting title in 1955. When his career ended in 1974, Kaline had won 10 Gold Glove Awards, played in 15 All-Star Games, and played for the World Series champions in 1968.

In 1974, Kaline became a member of baseball’s exclusive 3,000 hit club. As ballplayers go, he’s under-appreciated as a baseball great similarly to that of Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals. Maybe it’s the fact that both teams played in the midwest, I don’t know.

Kaline was only the 10th player inducted on the first ballot in 1980. Tigers fans that didn’t have a chance to see him play in his prime were able to watch him broadcast games with Tigers Hall of Famer George Kell. Kaline was a commentator from 1975 to 2002. These days, he can be found sitting in the executive suites watching the games.

This definitive bio is enlightening as Hawkins reveals stories that had never been told before, both on and off the field. It’s not only a must read for Tigers fans but all of baseball fans. Take it from me, I like learning about those in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Unfortunately for author Steve Aschburner, Harmon Killebrew passed away before he had the opportunity to write his life story in Harmon Killebrew: Ultimate Slugger.

Had the Killer not passed away, the book would have been one of those “As told to” type of biographies or memoirs but a las, it was not to be.

The Killer was one who drank milkshakes throughout his career. A power hitter, he finished with 573 career home runs. He’s known for having a warm, gentle personality but also that tremendous swing of his that defines what it means to be a power hitter.

Aschburner traces his life back to Payette, Idaho through the days of signing with the Washington Senators. When he retired with 573 home runs in 1975, he held the AL record for home runs from right-handed hitters for 37 years. The installment of the DH helped to prolong his career but the Twins had a DH in Tony Oliva so Killebrew sought out a deal with another franchise, the Kansas City Royals. While Killebrew played time between first base, third base, and the outfield, he was not the best defender in the game. He would have benefited from being a DH from the get go of his career.

While Aschburner did not have the chance to interview Killebrew, he was able to talk with friends and family. He covers how the 1953-57 seasons influenced the rest of his career. There was also the experience of the playing on the 1965 Minnesota Twins team that lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers in the World Series. Having lossed in 1965, he was on scene in 1987 as a broadcaster when the Twins defeated the Cardinals.

Like many athletes, Killebrew’s post-baseball life saw personal and financial struggles. He made some bad investments but having the chance to return to the Minnesota Twins as an ambassador was the best thing that ever happened for him.

The final chapters of the book were sad to read but when he passed away in 2011, he was remembered as the greatest Twins player of all time, a title that had been held by Kirby Puckett.

Don’t let the “Killer” nickname fool you. Killebrew had a demeanor that was kind and soft-spoken. This book celebrates his life and should be read by all baseball fans.

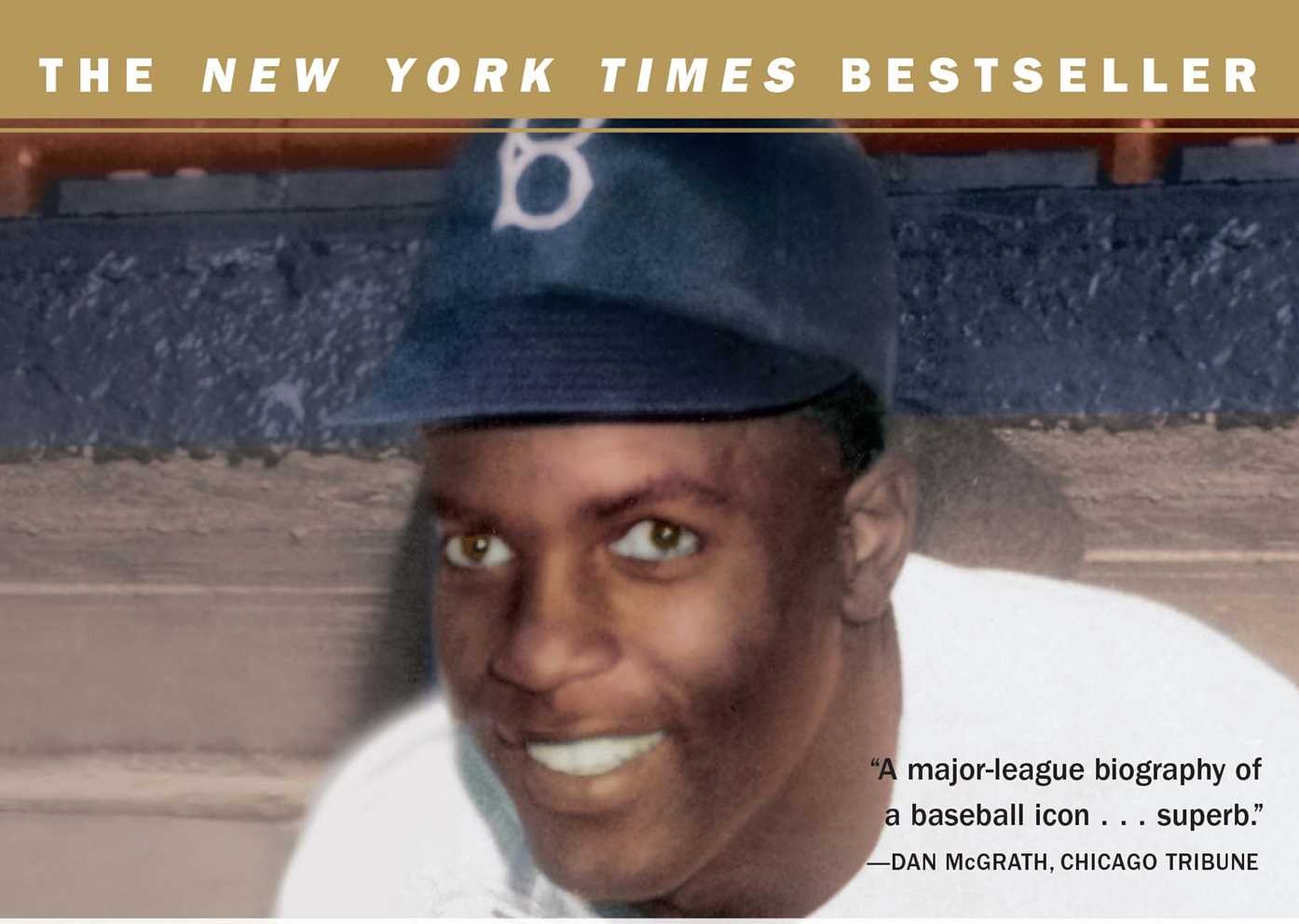

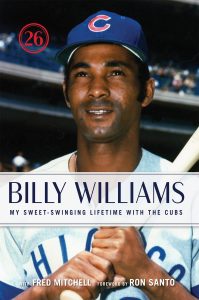

Billy Williams, with the aid of Fred Mitchell, shares his life story in Billy Williams: My Sweet-Swinging Lifetime with the Cubs.

The Chicago Cubs Hall of Famer nearly quit baseball in 1959. Had it not been for the legendary Buck O’Neil driving to visit him at his home in Alabama, chances are he probably would have been finished with the game. Instead, he’s devoted his life to baseball–most recently as an executive advisor for the Cubs.

In his memoir, Williams writes of the time he has spent as both a player and a coach. An entire chapter is spent reminiscing on some of his teammates. He goes back to the start of when he was growing up in Whistler, Alabama. With few opportunities to play the game, he got help from older players in the amateur leagues.

It was playing the minor leagues with eventual Hall of Famer Ron Santo that the great Rogers Hornsby told him that he would make it to the big leagues.

After nearly quitting in 1959, Williams quickly made to the Cubs roster.

In his book, he writes about the 1969 season and how it ties into Cubs fans today. He even offers some advice when it comes to hitting. Williams shares his memories of playing in 6 All-Star games and subbing for Musial.

After falling short with the Cubs, he reached the postseason while playing for the Oakland A’s in 1975. In 1987, he finally got the call from Cooperstown.

His story, while endearing, is one of determination and perseverance as he sheds light on the problems that he faced and what he was able to achieve as a ballplayer.

Williams became a Cubs coach in the 1990s and was there for the steroid era. He shares his thoughts on Sammy Sosa, including the corked bat incident, and his reaction to Al Campanis’ remarks on why there are so few African-American executives and managers.

Williams accomplished his dreams of reaching the major leagues and inspires others to do the same.

While the rest of the Baseball Hall of Fame Class of 2014 will be announced a week from yesterday, I’ve been busy looking at the books written by and about the members of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. It’s always interesting to read about what made a player the way that they are and what it was like to play in that era.

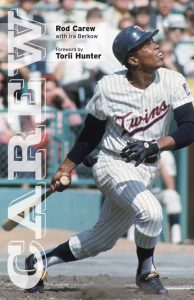

After finishing George Vecsey’s biography of Stan Musial, I immediately started on Carew by Rod Carew. Carew started his career out with the Minnesota Twins, where he played for 12 seasons. When his autobiography was originally published in 1979, he was finishing up his time with the Twins before heading west to play for the Los Angeles Angels, then known as the California Angel, for the final seven seasons of his career.

Originally published in 1979, the book was reprinted in 2010 with an afterward that explores the remainder of Carew’s baseball career and what happened in his life since. It’s an honest and forthright memoir that doesn’t ignore what happened off the field. Carew writes candidly about growing up in Panama and later Harlem, where he moved in his teenagers. Playing for the sandlot teams in the Bronx is what enabled Carew to be scouted by the Twins. Carew revisits the 1977 Twins season, where he hit for .400 only to fall short as the season wore on. But for a few brief weeks at the end of June and start of July, his .400 batting average was all the talk of baseball.

In his book, Carew writes about his philosophy and approach to hitting. Early on in the book, he tells what it takes to make it to the big leagues. It’s good advice for anyone that wants to play baseball or is currently in the minor leagues and wants to make the big leagues.

There’s the off-the-field issues, too, like growing up in poverty and dealing with an abusive father that he would not really talk about in the early years of his baseball career–not even with his wife. Because of his interracial marriage, Carew had to deal with racism. It’s unfortunate that he had to go through those events in the 1970s.

The afterword covers some highs and lows of his post-baseball life. While Carew was inducted on the first ballot in 1991, he lost his youngest daugher, Michelle, to leukemia. This, ultimately, led to his marriage breaking up. Carew would remarry in the early 2000s after taking a year away from baseball.

While talking about the Hall of Fame, Carew details why he chose to go into the Hall with a Twins cap rather than Angels.

Carew is highly recommended.

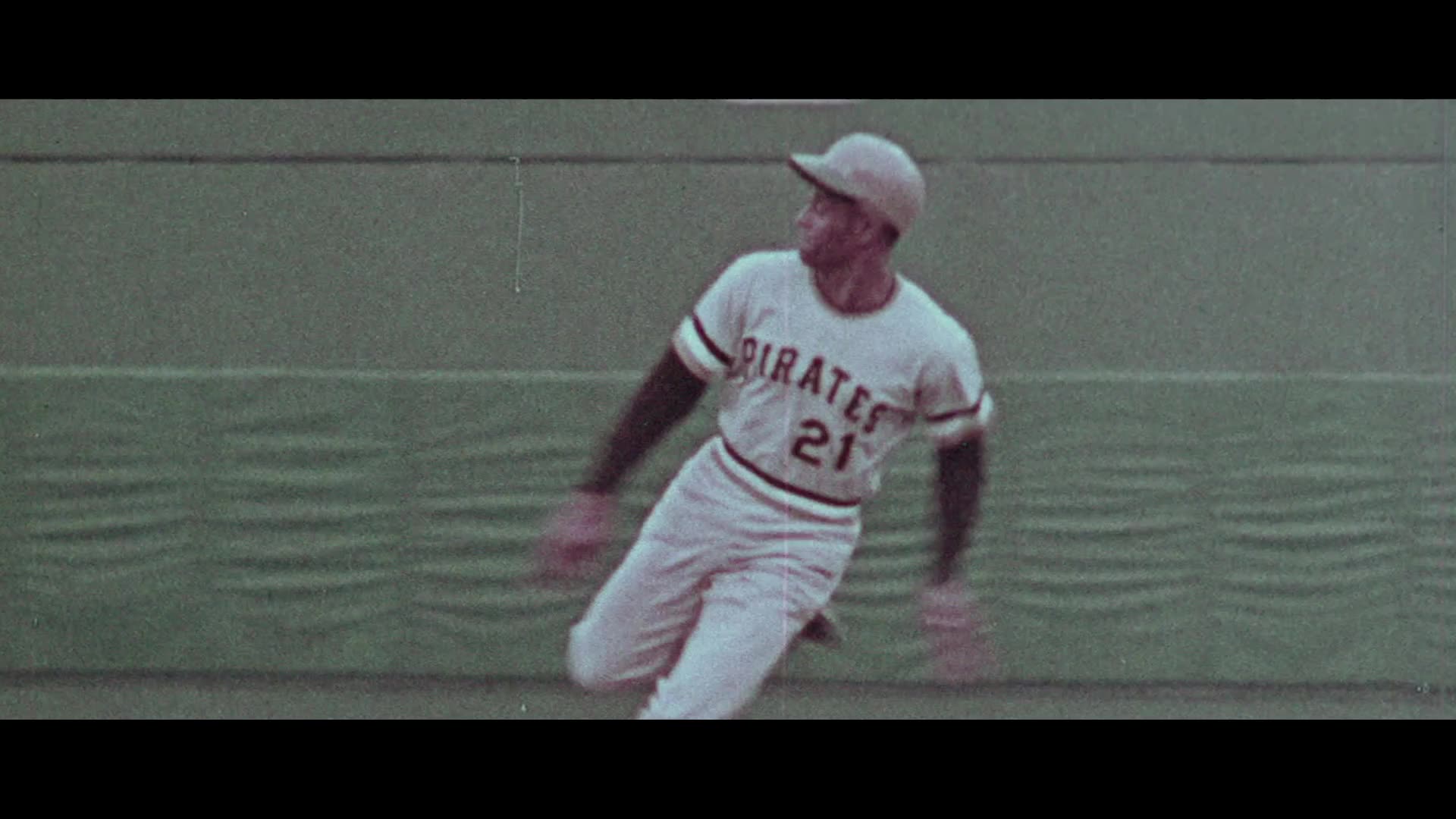

Like the Ralph Kiner and Roberto Clemente biographies, my reviews of books on Fergie Jenkins and Mike Schmidt appear to be forever lost to the internet. That’s what happens when an editor goes AWOL and they shut the site down.

Discover more from Dugout Dirt

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.