Lou Boudreau—with co-writer Russell Schneider—penned his memoir, Lou Boudreau: My Hall of Fame Life on the Field and Behind the Mic, back in 1993 when it was originally released under a different title by Sagamore Publishing. Sports Publishing gave it a new title upon reprinting the book in 2017. Jack Brickhouse and Chuck Heaton provide the forewords.

The Hall of Famer makes no mention of the Jewish ancestry on his mother’s side. Come to think of it, he doesn’t even really bring up religion at all. His parents were divorced and it certainly had an impact on him. His dad was the one who championed his playing baseball and lived just long enough to know that Lou made it to the major leagues. That being said, Boudreau does discuss some of the fallout when Cleveland GM Cy Slapnicka first offered him and his family money in return for playing for Cleveland after graduating from the University of Illinois. Suffice it to say, his stepfather wasn’t happy about not getting a larger share and wrote off to the Big Ten about Cleveland’s offer. It resulted in Boudreau losing his college eligibility. Despite this, he would graduate from college and coach some of the Illinois basketball teams when he wasn’t actively playing for the Cleveland ballclub.

When Boudreau penned his book, the baseball world was changing. In fact, the season would come to a premature end just over a year after the original May 1993 publication. The player-manager-turned broadcaster offered his thoughts on the changes to the game. One of the biggest changes was not just free agency but the amount of guaranteed money that players were making. Boudreau felt that it was more difficult for one to manager a ballclub during the 1990s.

Since free agency came into the game in the mid-1970s and players are able to sell their services to the highest bidders, individual statistics are most important, not the intangible contributions a player makes to a winning team. And when a player has a multiyear contract that’s guaranteed no matter what he or his team does, where is the incentive?

At this point in his life, Boudreau viewed the individual stats (batting average, home runs, runs batted in) as being what mattered most more so than various contributions that players did to help their team win. But for what it’s worth, he couldn’t fault players for taking the deals that they could get.

He added manager in addition to his role as player in 1942, making him one of the youngest “boy managers” in MLB history. Boudreau foolishly decided to ask of the press to let him know what they were writing before filing their stories with the respective newspapers. There are some things that managers shouldn’t do and that’s one of them. Cleveland Plain Dealer beat writer Gordon Cobbledick—who would become sports editor in 1946 and received the J. G. Taylor Spink Award, later renamed the BBWAA Career Excellence Award, posthumously in 1977—put him in his place. Neither Cobbledick or other beat writers were paid by the Cleveland ballclub but the newspapers.

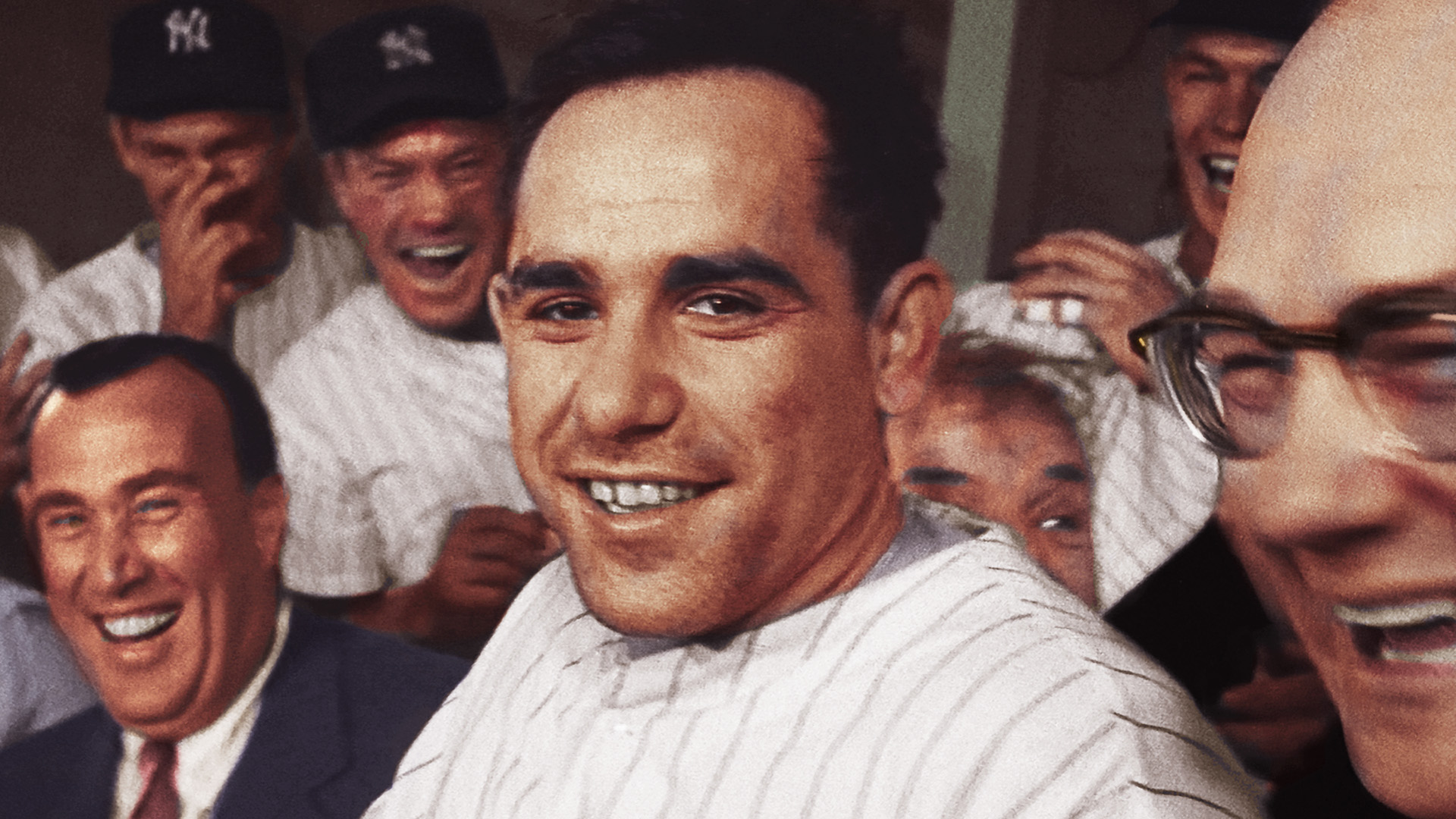

Boudreau’s time with Cleveland just happened to coincide with the ownership change from Alva Bradley to Bill Veeck following the 1946 season. It should come as no surprise that Boudreau writes plenty about the Hall of Fame owner, not to mention his own feelings about Hank Greenberg coming over as an executive. Boudreau had been Veeck’s right-hand man until Greenberg arrived after the 1947 season. The same offseason also happened to be when Veeck threatened to trade Boudreau to the St. Louis Browns for Stephens. Cleveland fans were not having it and preferred Boudreau stay. The result: Boudreau not only won the 1948 MVP but the ballclub won the 1948 World Series—one of two championships in club history. In addition to the Hall of Fame shortstop, this was a team that featured a number of future Hall of Famers: pitchers Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, and Satchel Paige; second baseman Joe Gordon; and outfielder Larry Doby. At Casey Stengel’s suggestion, Veeck asked that the Yankees send Gene Bearden in a trade—the pitcher won 20 games that year,

By the time he wrote his book, enough time had passed for the Hall of Famer to fully reflect on his career. He knows from experience that “you can never take a pitcher out too soon, only too late.” As he writes:

One of the toughest jobs a manager has is knowing when to replace a pitcher. It’s something I felt I never did well until after I managed a couple of years.”

Managers have a history of second guessing themselves no differently than fans are critical of their decision-making. It’s this insight that would allow Boudreau to later blossom as a radio analyst following his retirement from baseball. The same insight is also what led him to be hesitant to take the job, too. He didn’t want to appear to be too critical, having played the game for so many years.

After Boudreau retired as both a player and manager, WGN’s Jack Brickhouse—a recipient of the 1983 Ford Frick Award—recruited him to do radio for the Chicago Cubs starting with the 1958 season. This made him one of the earlier ex-ballplayers/managers to become a broadcast analyst, joining the likes of Dizzy Dean, Joe Garagiola, Phil Rizzuto, Ralph Kiner, etc. His knowledge of baseball came in handy during a doubleheader in 1976. The umpires suspended a game on account of darkness but because it wasn’t official, Boudreau knew that because the game wasn’t official, it would mean starting over from first pitch. The umpires confirmed it with the National League office and the Cubs were no longer down by two runs when they restarted.

Lou Boudreau’s voice comes through on every page of his memoir and if you want to learn more about his life and career, I definitely recommend it.

Discover more from Dugout Dirt

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.