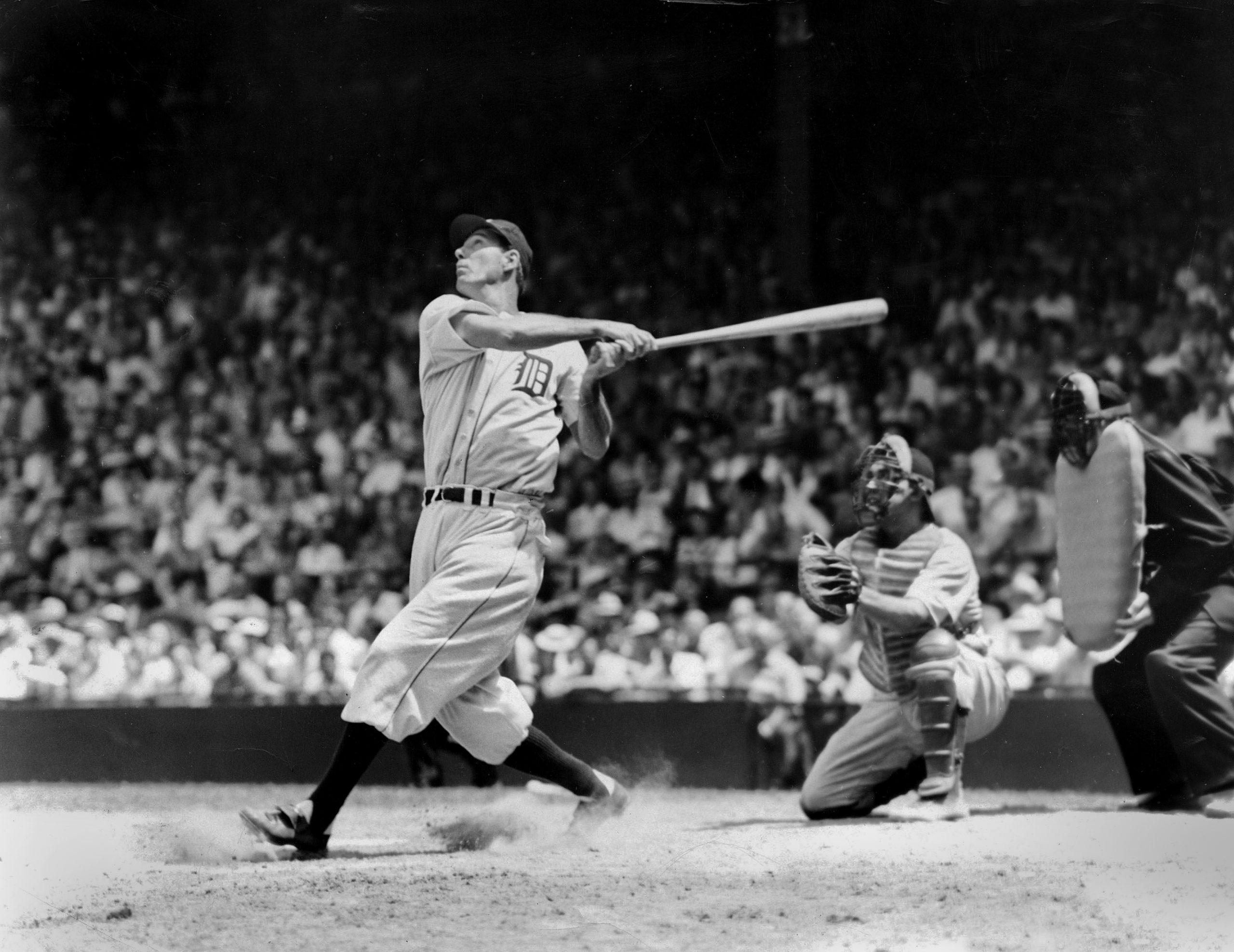

The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg has been remastered in 4K for a 25th anniversary re-release to mark 90 years since Greenberg took off on Yom Kippur in 1934.

When you’re a Jewish baseball fan, there are two players that you learn about early on: Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax. When my family visited the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 2001, I chose to have my photo taken with their plaques. To be fair, I did not have a digital camera at the time. No photos with Stan Musial, Bob Gibson, or other icons like Lou Gehrig if you can believe it. Meanwhile, I’ve been wanting to rewatch this film for a while now but the library did not have a DVD nor was it available through digital retailers. Lucky for baseball fans and Greenberg fans in general, the film is back in theatrical release starting on September 20. The film will open first in Detroit before a slow nationwide expansion.

The original Hammerin’ Hank was idolized by many, including late actor Walter Matthau. Matthau does not play tennis but joined the Beverly Hills Tennis Club just because of Greenberg being a member–he had many lunches with him. Family members, friends, fans, and Tigers teammates are among the interviewees. Tigers teammates include Charlie Gehringer, Flea Clifton, Billy Rogell, Birdie Tebbetts, Elden Auker, Harry Eisenstat, Hal Newhouser, and George Kell. Ralph Kiner is the sole Pittsburgh Pirates teammate on camera.

Greenberg had an Orthodox Jewish upbringing. His parents were not initially happy about his playing baseball. The New York Giants did not have interest but the New York Yankees did. However, they had a first baseman in Gehrig so Greenberg declined. When the Detroit Tigers scout reached out to Greenberg’s family, his parents were insistent that their son attend college. NYU did not work out so Greenberg signed with the Tigers after his freshman year. Greenberg debuted on September 14, 1930 against the Yankees in his only MLB game until returning in 1933.

Once he made his way to Detroit, he found it to be a hotbed of antisemitism. It was the home of bigots like Henry Ford and Father Charles Coughlin. Greenberg discusses the anti-Jewish hate in archival interviews. This hatred only drove him as a player, where he excelled as a hitter. He saw hate from the New York Yankees players, specifically whichever minor leaguer player got called up just to hate on Greenberg.

In 1934, Greenberg was having a very good season. The Tigers were fighting for the AL pennant but both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur were right around the corner. A 1934 headline in Detroit media stated that Talmud cleared the way to play on the holidays:

Henry Greenberg need have no pangs of conscience because he plays base ball during the Jewish holidays, or on Saturday, the Hebrew Sunday, which is just as important a day of rest and religious devotion as any of the annual church holidays.

The headline, for what it’s worth might be a slight exaggeration as the question was asked of Rabbi Joseph Thumim–my 10th cousin 6 times removed–then of Temple Beth Abraham, one of the oldest Orthodox shuls in the Detroit area. Rabbi Thumim soon clarified his opinion in the Detroit Jewish Chronical after being misquoted. When Rosh Hashanah came around, the Detroit Free Press was one of the first media outlets to wish Jewish readers a L’shanah tovah in Hebrew.

As Mishpacha notes:

According to the local newspapers, Rav Thumim’s pronouncement was rather nuanced and theoretical, stipulating three conditions for Greenberg to be permitted to play: no tickets were to be purchased by Jews on the day of the game, or carried there; there was to be no smoking at the game; and the concessions should be kosher.

While Greenberg played on Rosh Hashanah, he took Yom Kippur off, walking into Congregation Shaarey Zedek. Despite Greenberg not playing on the high holiday, the Tigers went onto when the AL pennant. Detroit would face the St. Louis Cardinals during the World Series, falling in seven games. The next season, the Tigers defeated the Chicago Cubs in the World Series. Furthermore, baseball writers would name Greenberg as the 1935 AL MVP Award winner.

Flash forward to 1938, Greenberg was closing in on Babe Ruth‘s single-season home run record of 60 home runs. Facing Cleveland during the last series of the season, Greenberg was unable to tie or break the record. Bob Feller set a new AL strikeout record with 18 in one game. Worse, no lights would mean suspending the game on account of darkness. The fact that Greenberg did not break the record also speaks to the antisemitism during this era. Stephen Greenberg said his father “never felt it was true” that people did not want him breaking the record. That’s not to say that there would not be an increase in antisemitism in Greenberg’s direction. Bund rallies took place all the time in the late 30s, no different than in Nazi Germany.

Greenberg grew more comfortable with his Jewish celebrity. Stephen Greenberg discusses his father’s feelings about home runs during the late 30s: “Every time he would hit a home run, he felt doubly proud because he felt like he was hitting a home run against Hitler.”

Greenberg made the switch from first base to left field during the 1940 season. The Tigers won another AL pennant in 1940, falling to the Cincinnati Reds in seven games. In his autobiography, the Hall of Famer admitted to sign stealing during September 1940. In any event, he won his second AL MVP Award, making history by becoming the first MLB player to win the MVP Award at two different positions. Little did anyone know that this would be Greenberg’s final season in his prime. After playing 19 games in 1941, he would join the U.S. Army after registering for the nation’s peacetime draft. His discharge would not come until December 5, 1941. Two days later, the U.S. was attacked on December 7, 1941. He re-enlisted, volunteering his services for the Army Air Forces. His 47 months of service were the longest of any ballplayer.

Returning as a 35-year-old ballplayer, Greenberg would never be the same. This is not to say that he did not put up great statistics because he could still hit the ball. He hit a home run in his return to the Tigers, almost as if nothing had changed. The Tigers would defeat the Chicago Cubs in the 1945 World Series in seven games. Back at first base during the 1946 season, Greenberg once again put up solid numbers. It would mark the end of an era for the Detroit Tigers as they would end up trading him to the Pittsburgh Pirates following a salary dispute.

To accommodate his hitting, Pittsburgh would build Greenberg’s Gardens in left field to help his home run numbers. The trade came just in time for Greenberg to not only become a mentor to Ralph Kiner but to show why he was a class act in a moment with then-Brooklyn Dodgers rookie Jackie Robinson. Their conversation came after a collision at first base. Greenberg knew exactly what Robinson was going through because they both suffered from racism.

The baseball writers would elect Greenberg to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956 with 85% (164 of 193 ballots). It took ten ballots for Greenberg to get elected by the BBWAA. The Tigers later retired his number in 1983 with fans giving him a standing ovation. A post-script alerts viewers to Greenberg’s post-playing career as an executive. After retiring, Greenberg would join the Cleveland front offices to work with Bill Veeck, first as Farm Director and then as part-owner and General Manager from 1948 to 1957. Cleveland would win the 1948 and 1954 AL pennants and take home the 1948 World Series. Greenberg would later become the Chicago White Sox principal owner from 1959-1961–the Sox won the 1959 AL pennant. At the end of the 1960s, Greenberg testified on behalf of Curt Flood regarding the reserve clause.

There are more interviews during the credits, including one where Maury Povich speaks of a discussion with his father, sportswriter Shirley Povich, about working on Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur. The younger Povich didn’t have much of a choice. A post-credits interview features comments from the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg discussing the U.S. Supreme Court and Greenberg’s legacy regarding the Jewish holidays.

Ninety years after Hank Greenberg took his Yom Kippur stand, The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg remains a must-watch documentary for baseball fans. If the film leaves you wanting more, make sure to check out Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes by John Rosengren.

DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Aviva Kempner

FEATURING: Hank Greenberg, Rabbi Reeve Brenner, Walter Matthau, Alan Dershowitz, Sen. Carl Levin, Stephen Greenberg, Joe Greenberg, Rabbi Max Ticktin, Bill Mead, Basil “Mickey” Briggs, Don Shapiro, Bert Gordon, Joe Falls, Dr. Leo Ribuffo, Dr. George Barahal, Ira Berkow, Harold Allen, Robert Steinberg, Charlie Gehringer, Herman “Flea” Clifton, Billy Rogell, George “Birdie” Tebbets, Ernie Harwell, Eldon Auker, Dick Schaap, Harvey Frank, Marilyn Greenberg, Harriet Colman, Max Lapides, Shirley Povich, Jane Briggs Hart, Harry Eisenstat, Bob Feller, Hoot Robinson, Hal Newhouser, Arn Tellem, Caral Gimbel, Glenn Greenberg, Alva Greenberg, Rep. Sander Levin, George Kell, Ralph Kiner, Maury Povich, Ruth Bader Ginsburg

The Ciesla Foundation is re-releasing The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg in theaters on September 20, 2024. Grade: 5/5

Discover more from Dugout Dirt

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.